This is Part 2 of a multi-part series exploring Compulsion and Compensation in our modern working life (click here to back to Part 1). I’m doing this partly through exploring my own personal biography, which, of course, is particular to me. But I hope to distill some parts of my own experience that also help you connect to yours. And, to take it even one step further, I hope to explore better relationships to work today, writ large, since I see such a lot of brokenness in this area of people’s lives.

Since I’ve worked as a teacher for most of my adult life, what I’m sharing comes from my experience of that world. However, I am quite sure that there is much that translates to many other types of work, perhaps nearly all of them.

Before launching Part 2, I also wanted to say a couple things here about sharing my own biography. First, I have to say that I have had amazing experiences being a teacher in general, and being a Waldorf teacher especially. I have loved my work, even as it has sometimes overwhelmed me. So, while I’m sharing some of the negative elements of my work with you all, in no way should it be understood that this is “sour grapes.” I have lived a charmed existence in my working life; a privileged one, in fact. I have had the privilege of loving my work. I’ve worked really, really hard too. And I regret none of it. We all work out our karma in and through our lives and our work. Of that much, I am sure.

Secondly, I’m also very aware these days of how being an Enneagram Type Four has shaped how my particular path has worked out. I’d encourage anyone who feels intrigued, puzzled, or bothered by certain patterns in their work or relationships to study the Enneagram. It can really help give insight into the way in which each of us is actively narrating and choosing our experience, and why we narrate and choose the way we do.

OK, let’s keep going, shall we?

Our salaries at the Waldorf school were typically low for being teachers at a small private school, probably even a little lower than most. As I’ve related, we also were asked to do more (or at least think of ourselves as being responsible for more) than most teachers are called upon to do. The ethos of the school where I worked was that the task of being a Waldorf teacher was a spiritual calling of sorts, even a calling of the highest kind! Monetary compensation was nowhere near where it “should have been” in terms of our education levels, skill, hours and days of extra time, care and attention to students and lessons, and great creativity that we poured in. But this fact just didn’t come up much. We believed (or were led to believe) that we were doing a great cultural deed and service, and that was reward enough. In a more nuanced way, perhaps it was felt that the school was a (sacred) community and so the rewards for working there went well beyond money and benefits. And I know that for me, for a long time, there was much truth to this.

Before Waldorf, I got my start in public education, and worked in three public schools in four years across two states. I posted an early memory of that time soon after I started this Substack here. They were “good” schools (meaning the property tax base was high and so they had many more resources than other schools not so fortunate), and the teachers I worked with at those schools were similarly dedicated, creative, often quirky, and self-giving. They also had a similar sense of performing an important cultural task, although there was much less concern for the administrative tasks of the school, as that was clearly in other people’s hands (the principal, etc). Although many of my fellow teachers were quite nice, there was even less collegiality than in the Waldorf school. Folks came in and did their jobs, and most did them well. Then they went home. Their private lives were their own affair and their “performance” as teachers was all that mattered. As an exception to this rule, I remember one 8th grade history teacher at the school where I worked in the swanky suburbs outside New York City. He was Jewish and took it upon himself to create and sustain a program in which 8th graders could learn about the Holocaust and then had the opportunity to speak to actual Holocaust survivors that lived nearby. Many of my public school colleagues looked askance at this kind of above-and-beyond dedication, because it made them look bad, and he was perhaps too personally involved, and too determined to put real history onto the plates of his students. There was a focus in the public schools where I worked on just doing one’s job, and doing it well, but no more.

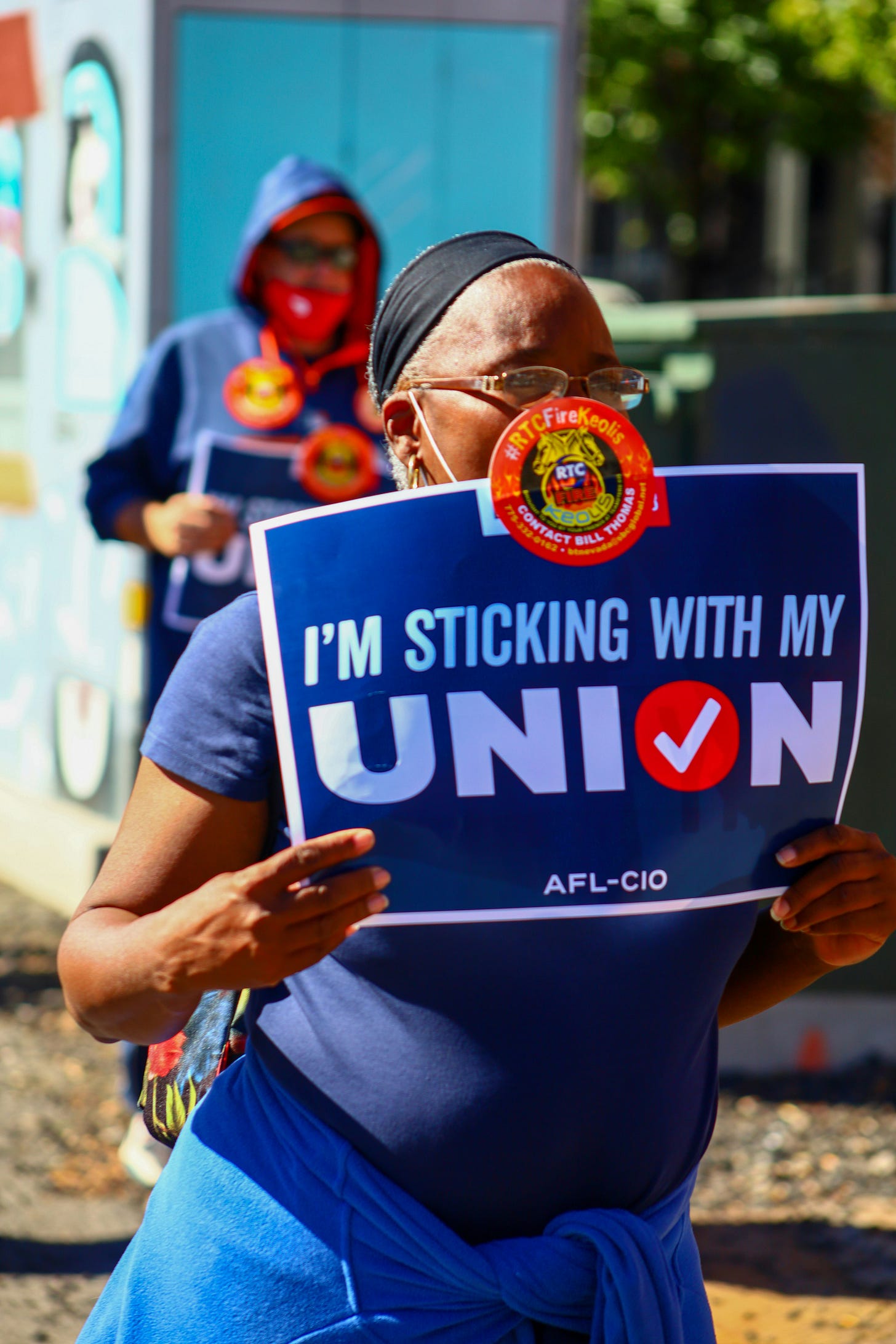

Those public schools, of course, had strong teachers’ unions. I was exposed to paying union dues for the first time when I worked in public schools, and nothing in my experience had prepared me for it. My parents had not belonged to unions, and, to my memory, nearly nothing had been said in my childhood about them, either good or bad. It’s so strange to me now as I reflect that I lived in Dearborn, just outside Detroit, the site of Ford Motor company headquarters, and some of the most historic union organizing and union-busting of all time, and no one taught me about it in my whole time going through my (unionized) public schools!

Anyway, I saw the dues deducted on my paycheck as a brand new teacher and mostly shrugged. I didn’t understand anything about what it was for, and I was making so much money compared to anything I’d made before, that I didn’t fuss about it.

A short few years later, when I’d left public school teaching, had moved to Chicago for grad school and took some classes from an influential professor, I started to learn some of that union history. My interest grew so great that I spent one summer in an internship with the United Food and Commercial Workers going to meat processing plants around Chicago and seeing the conditions of food factory workers. That same summer, I also had the task of attempting to organize church congregations in Joliet, IL to protest the new Walmart store that was moving in at that time (Walmart is an infamously union-busting corporation, although these days they look like peaceful lambs compared to Amazon). What an awakening this was for me! I’ve since then taken more classes, read some Saul Alinsky, Upton Sinclair and other writers and thinkers in union lore, and, given that I took it up later in life, I feel at least somewhat better educated about unions and union history than I was as a younger person. That experiential education that I received in my late twenties has led me to be a supporter of labor unions in general, as the one major social movement that has power to curtail some of the worst effects of unbridled capitalism. Until we invent an economic system that doesn’t exploit-by-design, we need strong unions, I’m convinced.

However, here is my observation: My friends that have stayed in public education (and are much better paid than I ever have been, vested in their pensions and protected by their unions) have not fared better than I in terms of burnout; in fact in some cases it seems much worse. I have several close teacher friends that went to work in the public sector at the same time I did, and stayed working at those same jobs all the way through. This leads to what to me seems like an incredible outcome: several of them at my age (right around 50) are near to reaching full retirement and full pension. They can retire! On the surface that sounds wonderful, except I see in some of them that “the school/system” has taken a heavy, heavy toll. The burnout that my friends in public schools have experienced is the same as mine, or worse. Cynicism about the students, the administration, and the parents abounds. In fact, they resemble those older teachers that I recall meeting when I was a fresh young teacher in my first year. Despite the fact that my friends have been vastly much better compensated than me, if anything they seem even more helpless and powerless to escape their ennui about the whole enterprise. I know several retired public school teachers who just plain won’t talk about their previous careers of teaching, at all, period. This tells me something interesting: that what is broken about school doesn’t really have to do with the money. At least not completely.

Thanks for reading, and as always I welcome your comments and insight. Your interactions help me shape my thoughts as I see how what I write reflects back to me through you!

Photo by Manny Becerra on Unsplash

Thank you for sharing about your teaching in the public sector and perspective on unions. I appreciate your thoughtful ideas and admire what a dedicated, passionate, and humble teacher you are. The Waldorf community is blessed to have you! My sister taught high school science in the NYC public school system for 10 years and had mixed feelings about being part of the union. Her teaching experience was vastly different from mine and I was always interested in hearing her stories and opinions.

Thank you for sharing your story and perspective!