Projective Geometry Lesson 8

The Father (or Mother) of Geometry Chooses Postulates

Last time, we spun a line around a point in our imaginations, which caused another point to slide along another line “to infinity” . . . and back again! I said that I’d explain and put some context around this Kepler’s Propellor thought exercise and the choice it leads to. One chooses from two possibilities. One may say that parallel lines “never” meet, and in that case one stays firmly in a Euclidean worldview. Or, one takes a deep breath and entertains the notion that two parallel lines do meet at one point “at infinity,” and then starts to explore the mind-bending consequences of that choice. I want to emphasize once more that there is no way to prove which choice is the correct one. Each one, if chosen, is an unproven assumption, a postulate. One has to simply take it as given and then see what results if one does so. Let’s explore just a little bit of math history for context about these choices.

Euclid lived around 300 B.C. in Alexandria, Egypt at a time when Alexandria was just being founded and becoming the great center of learning and culture that it did. We know almost nothing about Euclid as a person, except through things other later mathematicians wrote about him (or her!). What we do know is that Euclid had prodigious skill and a newly found desire to put mathematics on a rock solid foundation. There had been a number of generations of mathematics prior to Euclid, but it was all higglety pigglety and had been described in many different ways by many different people. Euclid’s strong inclination was to essentially go back to “first principles'' and re-prove it all, from the beginning. Euclid would gather all the scattered mathematics from all of history and the many varying methods, and put it all together in a towering logical edifice that was unassailable. It’s interesting to note that this is still how a lot of mathematicians behave today, as they do tend on average to be just a teensy bit OCD about making mathematics into a remote castle of unquestionable logic, accessible only to the initiated who speak a secret symbolic language, don’t they? But I digress. . . 😉

So, Euclid set himself the task of starting over. To do this, he intentionally placed himself in the position of saying “I know nothing!” He would not rely on any other mathematician's work, but would start only from the most basic of beginnings. Of course, Euclid realized that one couldn’t actually know nothing, because you can’t start something from nothing. So, he thought carefully about what assumptions he could make that were so obvious and indisputable that they could not be doubted. In the end, he came up with 5 Postulates, 5 Common Notions, and about 26 definitions. The Postulates were about geometry, the Common Notions were about mathematical operations (like adding, subtracting and changing order), and the definitions were just what they sound like, defining words (like “line” and “point” and “right angle”) that Euclid wanted to use.

Euclid strove to keep this beginning list as small as possible, since this was going to be the foundation upon which all of math would be built. Prior to Euclid was another famous Greek mathematician named Pythagoras. Maybe you’ve heard of the Pythagorean Theorem that relates the sum of the square of the legs to the square of the hypotenuse in any right triangle. Pythagoras had created an entire mystery school complete with acolytes, secret sayings and austere practices around the power of mathematics and number, and Euclid believed deeply in this power too. So, pursuing this task was not only an intellectual one, it was a spiritual one. Euclid was setting the foundations of the very universe through rigorous mathematical proof!

Only ideas that were absolutely needed, that were absolutely simple, and that were beyond question could make the list of Postulates.

So, now, I will tell you the five Postulates he chose, and let’s see how you react to each one. I suggest you read each one and then pause and see how obvious it seems, and how well you can picture it.

First, Any two points can be connected with one line. . .

Second, Any line can be extended as long as you need it to be. . . .

Third, You can draw any circle with a given center and radius. . . .

Fourth, Every right angle is congruent (equal to) every other right angle. . . .

(Pause for dramatic effect) . . .

.

.

.

Fifth, If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side of it taken together less than two right angles, then the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which the sum of angles is less than two right angles.

Wait, what????

That last one is a doozy and seems so terribly out of place, doesn’t it? Can you even picture it? I will make a drawing to help you out:

Euclid is imagining two lines at a jaunty angle to each other (i.e. not parallel) with a third line that is sometimes called a transversal cutting through them both. Then (recall for just one moment your high school geometry classes!) we label the two interior angles on the same side of the transversal. Now, if you add those two angles together and the sum comes out less than “two right angles” (meaning less than 180°), then, Euclid is saying, that side is the side where the two lines will meet at one point. Whew!

This fifth postulate is famous in the annals of mathematics for a couple different and related reasons.

Firstly, it is so deeply puzzling that it seems to be not nearly as simple as the other four, not even close. This can lead (and it has led) many mathematicians to question, “Did Euclid make a mistake?” Isn’t there something simpler there that he could have used, or maybe he didn’t need the Fifth Postulate at all?

Consequentially, as you may imagine, mathematicians for the next 2000 years (!!) tried and tried and tried to find an alternative. A number of mathematicians found alternatives, but they amounted in the end to restatements of the same postulate from a different perspective. Other thinkers tried making do without the fifth postulate altogether, but that was doomed too. So, it became clear as the centuries went on that Euclid knew what he was doing. For as strangely complex as it seems, and as different from the other statements, this postulate was absolutely necessary to prove all of geometry at the time. This is why Euclid has been given the title “Father of Geometry,” or sometimes “Father of Mathematics,” since back then geometry basically was mathematics. Yet, as I keep saying, Euclid could very well have been the Mother of Mathematics because we know nothing about her! Anyway, she started the ball rolling of all of this formalizing of mathematics starting from basic axioms or postulates and using deductive logic as the gold standard for how anyone can be sure that any knowledge is rock-solidly true.

With the benefit of hindsight, one can see something else, too. Euclid thought this through very carefully indeed. Notice that the way in which Euclid worded the postulate purposely ignores the parallel case! The postulate talks about which side the point is on when the angles add up to less than 180°. That of course implies that if the angles add up to more than 180°, then the point of intersection is not on that side, but the other side. But, this postulate is intentionally silent about when the angles equal 180°, in other words when they are parallel. Euclid seems to have understood that there was something impenetrable about parallel lines. . . and she/he avoided it.

Mysterious and intriguing, yes? I hope so! Next time, we will start to explore the real implications of accepting the “point at infinity” on any line. This will take us further and further down the rabbit hole and, I hope, cause each of us to start to awaken a bit to how much we take for granted in our intuitions about space, what is “really real,” and just how active we really are in the background of our lives in constructing our reality!

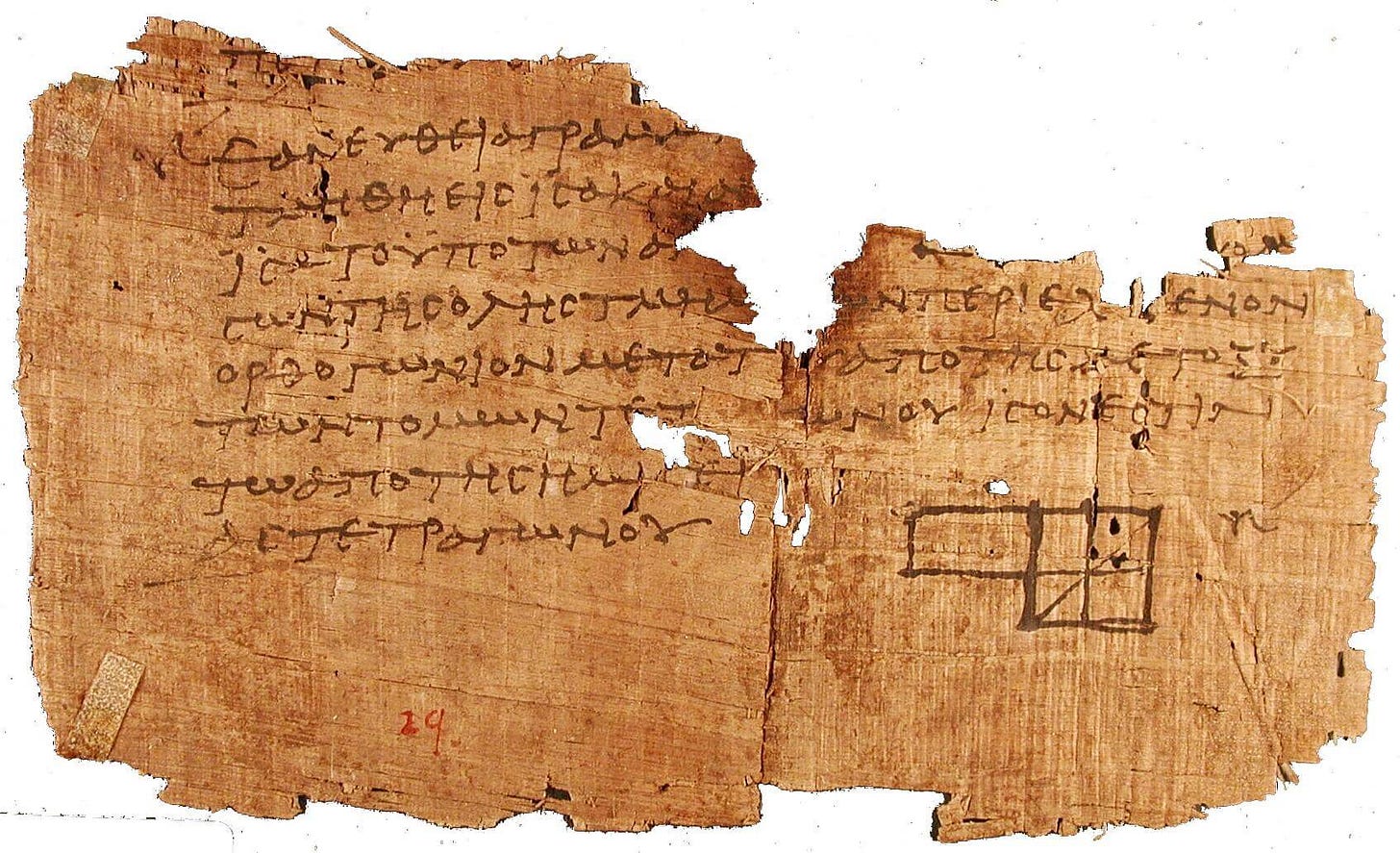

Image taken from Wikipedia. A papyrus fragment of Euclid's Elements dated to c. 75–125 AD. http://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/Euclid/papyrus/tha.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1259734