Peter and I are getting closer to finishing another installment of School is Broken, but in the meantime, I’ll put this out as an interlude that is nevertheless a related little mental cul-de-sac that I find myself in often. I hope you enjoy:

I’ve just finished a three week stint at a lovely Waldorf school, and it’s been a blast. I feel so very lucky to be able to come as a guest teacher and work with some spectacularly healthy kids and teachers. When compared with a lot of school communities out there, some of which I’ve experienced myself and others through teacher friends of mine, there is almost no comparison. Waldorf schools are just better. There, I’ve said it. They have way more beauty, kinder and gentler ways and transitions, exquisite artistic expression, beautiful music floating through the hallways . . .They have a much better connection to nature, a sane and at least potentially humane approach to teachers' work, and the teachers have so much individual freedom to bring the curriculum as they see fit. I often play it a little cagey when I’m writing here, so as to give fair treatment to other ways of schooling, but there is no doubt, I think Waldorf is tops. I don't claim to have direct experience with every kind of schooling out there, but, as my next door neighbor in Chicago, Robert, used to say, "I know a thing or two about a thing or two."

Let me be clear, however. Just because I think Waldorf schools are the best that I know about, that doesn’t mean I think Waldorf schooling is objectively “the best” over every other kind of school out there. That would be extreme hubris. Basically, as I’ve said before and took from Charles Eiseinstein, I hold opinions, but I hold them lightly. Also, just because I think Waldorf schools are really, really good, this doesn’t mean I think that there aren’t other really really good schools and homeschooling parents and cooperatives out there. There are as many good ideas about educating ourselves as there are places in the world with people in them, and no experts or educational gurus are necessarily needed.

Yet, I want more and more people who feel like they want to, to learn about Waldorf methods; I want to spread the wealth. And the wealth, believe me, is plentiful. There is so much that other schools could learn by giving Waldorf more attention. It’s a real mystery to me why, for example, Montessori has become so much better known, and Waldorf remains a strange open secret except to those who’ve experienced it. Once, when I was a full time Waldorf teacher, we were all given a professional development day to visit another school in Chicago and have a “cultural exchange.” I chose the Chicago Lab School and spent the day hanging out with their science teachers. It was a fine day, the teachers were smart and the facilities were impressive. I saw lots of things that I recognized from my public school teaching days. Near the end of the day, my host and I sat down and he started asking me about Waldorf methods. I did my best to describe it to him. I had tried earlier in the day with other teachers I met, and mostly I got blank looks that indicated to me that they didn’t get it. But this teacher listened well, considered what I told him (things like we use no textbooks, we try to teach directly from experiences of nature, we work from whole to parts, etc), and he said, after some pause for thought, “Wow, that sounds hard.” Indeed.

Yes, I think part of the mystery is simply that trying to be a Waldorf teacher is harder. One takes on much more responsibility than a typical teacher does. For one thing, you are supposed to be working on your own meditative life and generally trying to improve yourself as a human being! For another, you are expected to be generating original content from your own study, not relying on the content of experts. . . AND, you are supposed to be practicing a wide variety of arts, AND you are supposed to be taking the day’s activities consciously into your sleep life . . . There’s more. It’s a lot. I love challenging things, so mostly I lapped this up when I was doing my teacher training, although I’m still a little intimidated by chalkboard drawing and sculpture. Not my strengths, but I have learned to enjoy working on them. I still can't knit, however.

This all sounds pretty high-falutin’ doesn’t it? You might think I’m saying that Waldorf teachers are just better people. But that’s not really what I’m saying. Rather, I’m saying that the Waldorf method, as strong as it is, has this high bar built into its philosophy, and that, perhaps, this is simultaneously its strength and its Achilles’ heel. Because of these very high standards, I think Waldorf has appealed only to select groups of people with certain predispositions. Some of those groups I’d identify as either the very philosophically and/or artistically inclined, and those steeped in the humanities. Myself, as a science guy with no strong humanities or arts inclinations (at least on the surface), but plenty of religious/philosophical propensities, made it into the fold I think mostly through my aforementioned attraction to things that are hard work, plus a good amount of initial naivete. Basically, I dove right in because it looked beautiful, interesting and difficult. That’s my jam.

How can one bridge the gap between Waldorf and the wider world of education? Well, I am trying to do that right now by writing this. The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America has, to its credit, been trying very hard to provide accessible and understandable content that folks can read if they have an interest. This is a challenge in Waldorf: many of us want more and more people to gravitate toward Waldorf methods, but those methods are so counter-cultural that a lot of people find it hard to see value in them, unless they experience them directly.

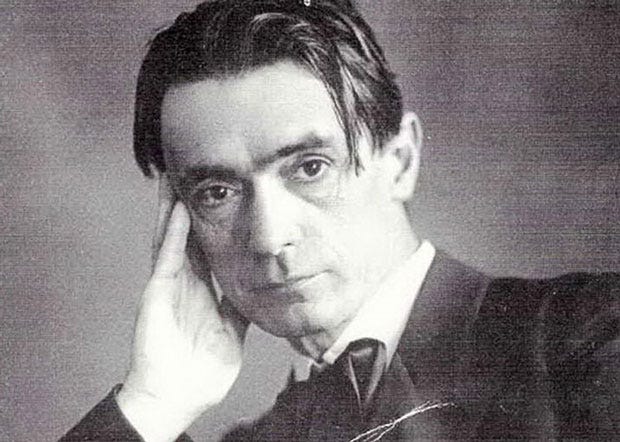

It’s possible that we are doing all we can already. I mean, how can you explain anti-materialism to someone that hasn’t got a clue that there is even another option? Rudolf Steiner tried to do this once in the early days of the first Waldorf schools, with some success as I understand it. That’s how the first school got its start. The school was so-named because it was begun for the children of the workers at the Waldorf Astoria cigarette factory. The workers asked for the school to be created after listening to Steiner speak. The owner of that factory, Emil Molt, was a follower and deep supporter of Steiner and his ideas. Steiner said something like this to those workers (paraphrasing because I can't find the direct quote right now): “The facts are as follows. I look into the world and see everywhere a picture that appears incomplete. Then, I look into myself and find exactly the missing pieces which I perceived in the world. Now I know that the world and I are poles of a larger reality that encompasses both." Seems simple, but goes against the grain of some of our deepest assumptions in popular culture today. I found an excellent video of a lecture given by the scientist/philosopher Rupert Sheldrake that is a nice introduction to anti-materialistic notions. The more we can do to wake people up to this, the better.

In my view, some of the resistance to spreading the message more widely comes from within as well. Waldorf teachers, because of all the extra expectations, can, quite humanly, start to think of themselves as very special indeed. Or, they start to value the nurturing nest that is the Waldorf school environment and stop worrying overmuch about whether what's happening in the school is in any kind of meaningful conversation with the rest of the world. Lots of parents discover Waldorf when their kids are at a very young age, and there is a very common occurrence of being overcome with the beauty of it all when they first walk in the doors and see a Waldorf early childhood classroom. Often they’re weeping tears of joy.

Contrast this with another frequent experience: that a good percentage of parents choose to withdraw their kids from Waldorf at around the end of 5th grade. Typically, and perhaps stereotypically, although certainly not always, the driving parent in making this decision is the dad. At about the same time, a good number of new kids transfer to Waldorf from other schools. Often the kids arriving have had difficulty at other schools and/or are neurodivergent in some way or another. This gives Waldorf a nice, quirky reputation for being a “land of misfit toys”, something I've thoroughly enjoyed as a teacher over the years. We get to teach some really cool, strange kids, and they usually find a safe nurturing environment when they come. I think teaching those kids over the years has allowed me to more openly embrace my own weird uniqueness.

But still I wonder. Why can't Waldorf ideas be applied in more, and more diverse, contexts? Why can’t we keep the families that leave in 5th grade and keep the new kids that show up, too? Why can’t we have more programming that is Waldorf-inspired but is diverse, unique and maybe doesn’t look like every other Waldorf school? Why can’t Waldorf make it into the public schools in a bigger way? There's an entire organization devoted to this, the Alliance for Public Waldorf Education. I’m thinking I need to get more involved with them, because this is the thing that really interests me. There’s a brand new public Waldorf high school that just started up near Amherst, WI. Another Waldorf school I’ve been working with for ten years is in the process of changing over to a public charter school. The “scuttlebut on the street” about public Waldorf initiatives is that the bureaucracy and rampant Ahrimanic tendencies of public schools eventually squeeze the life out of public Waldorf schools, and I’ve witnessed this myself, firsthand in at least one school I know of personally, and indirectly in schools I’ve worked in. Yet, we must try. The ideas are just too good.

In Waldorf circles, there’s a lot of “Rudolf Steiner once said. . .” sayings. One of these that I was told was this: “Rudolf Steiner once said” that someday, there wouldn’t be a need for Waldorf schools because the ideas by then would have made it out completely to the wider population and so every school would be a Waldorf school and hence the name wouldn’t be needed anymore. We are definitely not there yet, but I’d like to do my part. I don’t generally think starting another new Waldorf school is my way to do my part, since here in my town there are already so many little charter and choice schools with their own little ways and philosophies. Competition for students and shoehorning yet another school onto the landscape is not the way to spread good ideas. It’s got to be more like mutual pollination and fructification, like the way honeybees spread all over the landscape and uplift all the plants and trees with them. That’s what I’m going for.