Today, I want to revive what I started last winter, the beginnings of an exploration of Projective Geometry. I wrote ten posts in quick succession while I was teaching it, then had to rush on to the next thing. But I regard this work as only just begun, and when I have time to take it further, I will! Here is one more step.

I fondly remember the Sesame Street programs of my youth. Back then, Sesame Street episodes were pieced together with little montages that they would intersperse with the doings of the puppets and people. So, a new episode of Sesame Street would often have repeated montages that for whatever reason the producers chose to reuse. One that came up many times and that I remember so clearly was the song, “That’s about the Size, Where you Put your Eyes”. Do you recall that one? Let’s see if I can find it on YouTube. Yep, here it is. Boy, that brings back warm memories. Every time it came on, I was fascinated by this video and the idea that one could change one’s perspective and the little can become big, or vice versa. I especially appreciate that the video does not “zoom in” to imagined regions like the atomic or subatomic, since that creates the impression that one could see in those regions. One could not, and one can never, see the subatomic realm. That is because, as I’ve written about quite recently, that realm is a reductionist model that depends entirely on the restrictions and mathematical structures that sustain it. . . it is not anywhere near as “real” as the grain of sand that the ant is working with in the video. And yet, the experiences of changing perspective, of zooming in and zooming out are quite real, aren’t they? And, with the use of microscopes and telescopes, we are able to extend the “range of zoom”. The video does zoom out into our solar system and shows the planets revolving around our Sun. The change of perspective, the exploration of “outer space”; I hope it’s clear that all of this is entwined with Projective Geometry. Projective Geometry is a logical/mathematical but also an aesthetic/experiential/intuitive exploration of “zooming in and zooming out”, moving between “the point”, and “the periphery” to use a couple phrases that Waldorf folks often use. It may seem at first to be abstract, but the more one works with it, the more one can see how it frees up rigidities that we all carry around that prevent us from seeing more.

Back in Lesson 8 I described Euclid’s five postulate, five common notions and 26 or so definitions. What I haven’t explained yet, however, is how Euclid defined a point, and I want to dwell on this here for a while and allow it to expand our thinking. Euclid defined a point this way: “A point is that which has no part”. This is older language that is a little difficult to understand, but I understand this to mean that a point has no depth, length, or breadth. It is indivisible, it is pure location, without any internal structure whatsoever, and it takes up no space at all. Dwell on this for a moment please, not only with your thinking, but with your feeling. A point is nothing at all but a location in space. Reach out with your intuition and see how that feels to you. Does it feel a little… ungraspable, like a wil-o’-wisp that you can kinda see and kinda can’t? Many mathematicians since Euclid have explored the mathematics of the “infinitesimal” as it’s called, and some of this mathematics led to the development of Calculus, that Holy Grail of Math today that has terrorized and discouraged countless generations of students (yes, you do sense my grumpiness about how Calculus has been used a weapon of torture. Why do we do that? But, I digress).

The feeling you get when you contemplate what a point really is, and what it isn’t, is the feeling of “zooming all the way in”. It is exactly complementary to the feeling you get when you “zoom all the way out”. So, in the exact same manner that we can ask “What is a point?” (pure location in space), we have to immediately then ask “But, then, what is space?” If you are following me not only in your thinking but your feeling and intuition, you can maybe perceive that space is just as wispy a concept to grasp as a point. Looking at the definition of the point we’re working with and just mirroring the idea behind those words, we could say, “Space is pure extent with no location”. And it’s really notable that Euclid, as careful as he was, as brilliant as he was, as logical as he was, felt no need at all to define space. He took it entirely for granted. This is part of the great blind spot that Projective Geometry tries to bring into view (and that Calculus also ignores), that we are fixated upon points and lines, and take the space in which they must reside in order to exist entirely for granted. Space is a usually unobserved player in the 3-D world that we construct in our minds.

One more thing before diving in deeper: I want to “point out” (pun intended!) that lines and planes share some of the same weirdness as points. Lines have only length and no depth or breadth at all. They only “exist” in one dimension. Planes have length and width but no depth (so only 2 dimensional existence). And, if you “move your mind’s eye” and “look” at a line head-on, right down its length, it looks like a point. Whereas, if you look at a plane edge-on, it looks like a line.

To more firmly understand what I am saying, try this series of connected mental exercises. There are a bunch of them so go make a cup of green tea or something and get settled. Start by imagining a point in your mind.

Now you could imagine that point as just a point (although, as I’ve just tried to show, if you explore that imagination beyond the naive, you can start get a little queasy about what, exactly you are imagining!). But you could also imagine that point as the intersection of many, many lines. Start by imagining the point in a plane, and then imagine two lines, both also lying in that plane, both passing through that point. Now keep adding lines that intersect exactly at that point. If you drew this on paper, the point of intersection would get crowded and obscured pretty quickly, but if you do it entirely in your imagination, you are not restricted physically in this way…so, how many lines can you “draw” in your imagination that pass through that point? If your answer is something like “as many as I want,” or “an infinite number” you’re correct! Perhaps this exercise helps emphasize the weirdness of a point. One single point can “contain” an infinite number of lines. You may balk at that word “contain” (in what sense does a point contain a line? Isn’t it the other way around? you might say.) but remember we are working with deep intuitions and biases about space. For now, let’s say that “contain” simply means something like “is inextricably connected to”.

Now, transform this mental picturing to 3 dimensions and imagine a point in space, and all the lines coming in from every direction that pass through that point. Really try to imagine it, lines “shooting” or “streaming” into, or out of, this single point. Can you picture it? Perhaps it reminds you of a sunburst, or a dandelion gone to seed. . . .Now, how many lines can there be? Again, the answer is as many as you want, or an infinity of lines. So, again, a point, which has no dimension whatsoever, can contain an infinity of lines, this time not constrained to a plane, but coming from every possible direction.

Now, here’s one that for most people is harder to picture: Again imagining the point in 3-D, how many planes can you imagine that all intersect at that point? Since the planes can come in from any angle they want, there must, again, be “as many planes as we will ever need” all available and connected to that single point. If you are having trouble getting started on this imagination, you could begin with the good old x, y, and z planes of the 3D axes that you learned in high school math class. The point they all pass through is called the origin, remember that?…but you don’t need to stop at the three special planes that are mutually at right angles. You could keep adding planes at any jaunty angle you want, and make sure that they all pass through that origin. As many planes as you please can pass through that point.

Now, reverse this imagination (take breaks whenever you want to rest your imagination for a moment!). This time imagine a line, and ask yourself, how many points can you fit onto that line? This one is often easier for people to imagine (a sure sign that we have what I call a “point bias” in our thinking) And again, the answer is the same, you can place an infinity of points on any line, or you could say a line “contains” an infinity of points. (Does this use of the word “contains” feel more appropriate than using it above?) Do the same mental exercise for a plane, and ask how many points can a plane contain? Again, infinity, which is really saying “there is no upper limit to how many points I can put into a plane”. What about how many lines a plane contains? Again, an infinite number. Can you picture them, all pointing every which way in the plane, crisscrossing like an infinitely flat bundle of spaghetti?

Go through these imaginations enough times, and perhaps you can start to see a beautiful symmetry (and a lot of infinities!). Let’s collect each of these imaginations and use some words to describe these relationships between points, lines and planes in 2D and 3D space. Use the statements below to try all of the imaginations again.

First, let’s work in two dimensions (working on/in a single plane):

Two complementary statements about points and lines, working in a plane.

1A. A point in a plane contains an infinity of lines (all lying in that plane).

1B. A line in a plane contains an infinity of points (all lying in that plane).

Then two general statements about the plane itself.

2A. A plane contains an infinity of points.

2B. A plane contains an infinity of lines.

Now, in three dimensions (working on/in 3D space):

Three sets of complementary statements about points, lines and planes in space:

1A. A point in space contains an infinity of lines.

1B. A line in space contains an infinity of points.

2A. A point in space contains an infinity of planes.

2B. A plane in space contains an infinity of points.

3A. A plane in space contains an infinity of lines.

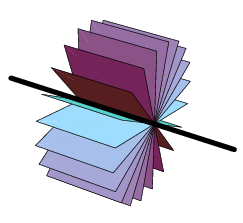

3B. A line in space contains an infinity of planes. (I didn’t have you try to picture this one yet. Can you? It’s often called a “sheaf of planes” all sharing one line.)

And, again, some general statements (this time, not two but three) about space itself:

3A. Space contains an infinity of points.

3B. Space contains an infinity of lines.

3C. Space contains an infinity of planes.

Are you still following me? Do you see that, in fact, points and lines (in 2D) and points, lines and planes (in 3D) do not have their own existence separate from each other, but co-arise, and that they all have a relationship to the “containing” plane (in 2D) or space (in 3D)??!!

It’s a deep thought, but if you can intuitively feel its truth, you can immediately see why trying to deeply think about what a point is, is exactly the complementary feeling to trying to comprehend what infinite space is. In other words, “zooming all the way in” and “zooming all the way out” are actually a kind of breathing between two poles that gives rise to both space, and the locations within it. Said in yet a third way, the moment you place a point in your imagination, you have also created all of the infinite space around it, whether you are aware of it, or not.

I know it sounds like I’m talking about deep philosophy right now, but the crazy thing is, all of this is logical and something that can be shown in a million different ways through drawing exercises in Projective Geometry. I’ve already started to show you some of those drawings, and I hope we will do more now that we’ve established that the points, line, and planes, and space itself, are all entirely conceptually interconnected, and we need to pay attention to them all, not ignoring one while focusing entirely on the other.

Cheers for now, my Projective Geometry students!

Here a depiction of that sheaf of planes all lying in one line if you were having trouble with picturing that one! But of course, you have to imagine the planes stretching out infinitely, and that there are an infinity of them!

A great example from nature of lots of lines coming in to meet at points! A sure sign that Nature knows how to “work with the periphery” quite well, while we are catching up to her due to the limitations of our point-biases.

Superb, including the link to Sesame Street! Just one thing confused me. When you wrote:

"Three sets of complementary statements about points, lines and planes in space:",

you labelled the statements 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 3C and 3D. I expected 3A and 3B. Was there a reason for this?

My neuro-divergent brain is always looking for patterns - which is why I love projective geometry! The polarities of point and plane with the line as intermediary is for me truly magical. Thanks for this. Now I need to find lessons 1-10 :-)

And if I may also share, I recently had an epiphany when I realised that the infinitely small inward point and the infinitely large peripheral plane are called the *ideal* point and plane, not because they are perfect (though perhaps they are) but because - like *Ideas* - we can only see them with our minds.

My ambition is to understand the space and counterspace research of Nick Thomas. The mathematics is beyond me but the ideas described strongly indicated support for many of the natural scientific teachings of Rudolf Steiner that I had otherwise struggled to understand.