“Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

Albus Dumbledore in Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows by J.K. RowlingContinuing on from my post yesterday, in which I used Zaphod Beeblebrox and Carl Sagan to get you thinking about How Big is Space, Really?

From here on out, I’m going to assume that you’ve read and tried the previous 11 Lessons in PG so far, and you’re ready to stretch further. So, if that’s you, let’s go! If that’s not you, feel free to give it a try anyway, and at the end, there will be some explanation of the significance of what we are doing here that you might want to still take in.1

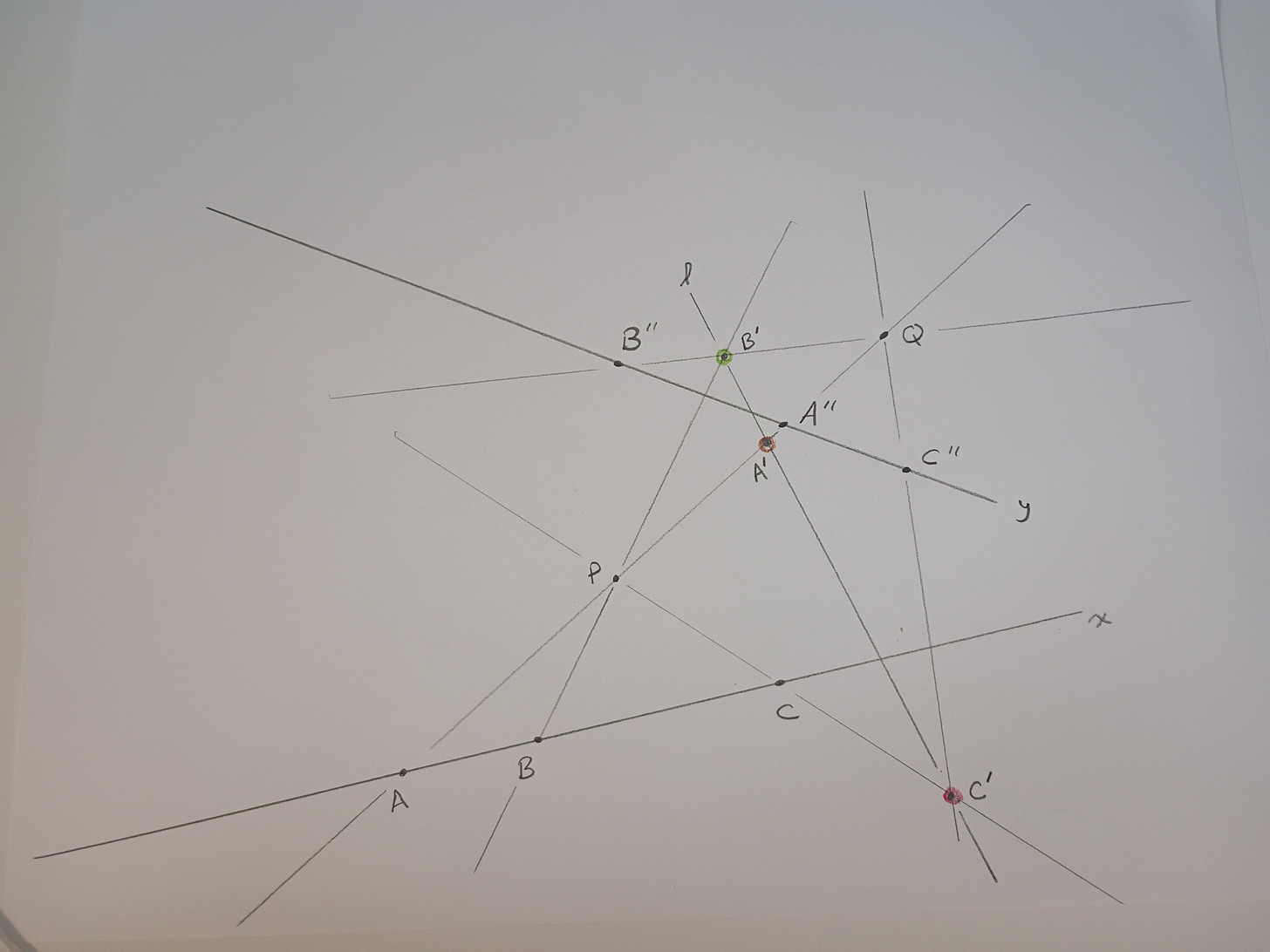

This is called The Fundamental Theorem of Projective Geometry, and as the name implies, is recognized by mathematicians as a core concept. We are working in a 2D plane for now, so we can draw on an ordinary sheet of paper as we have done before.

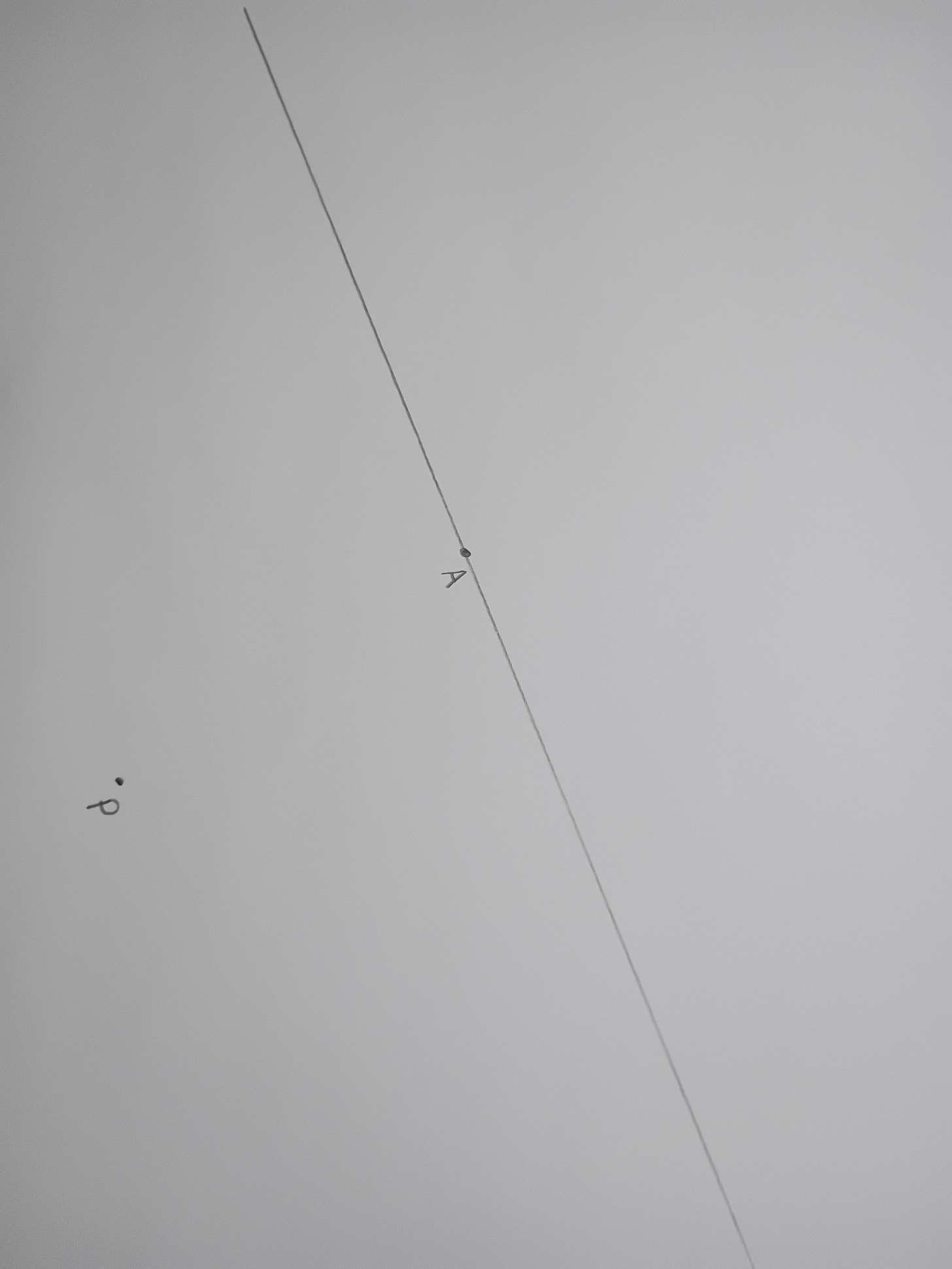

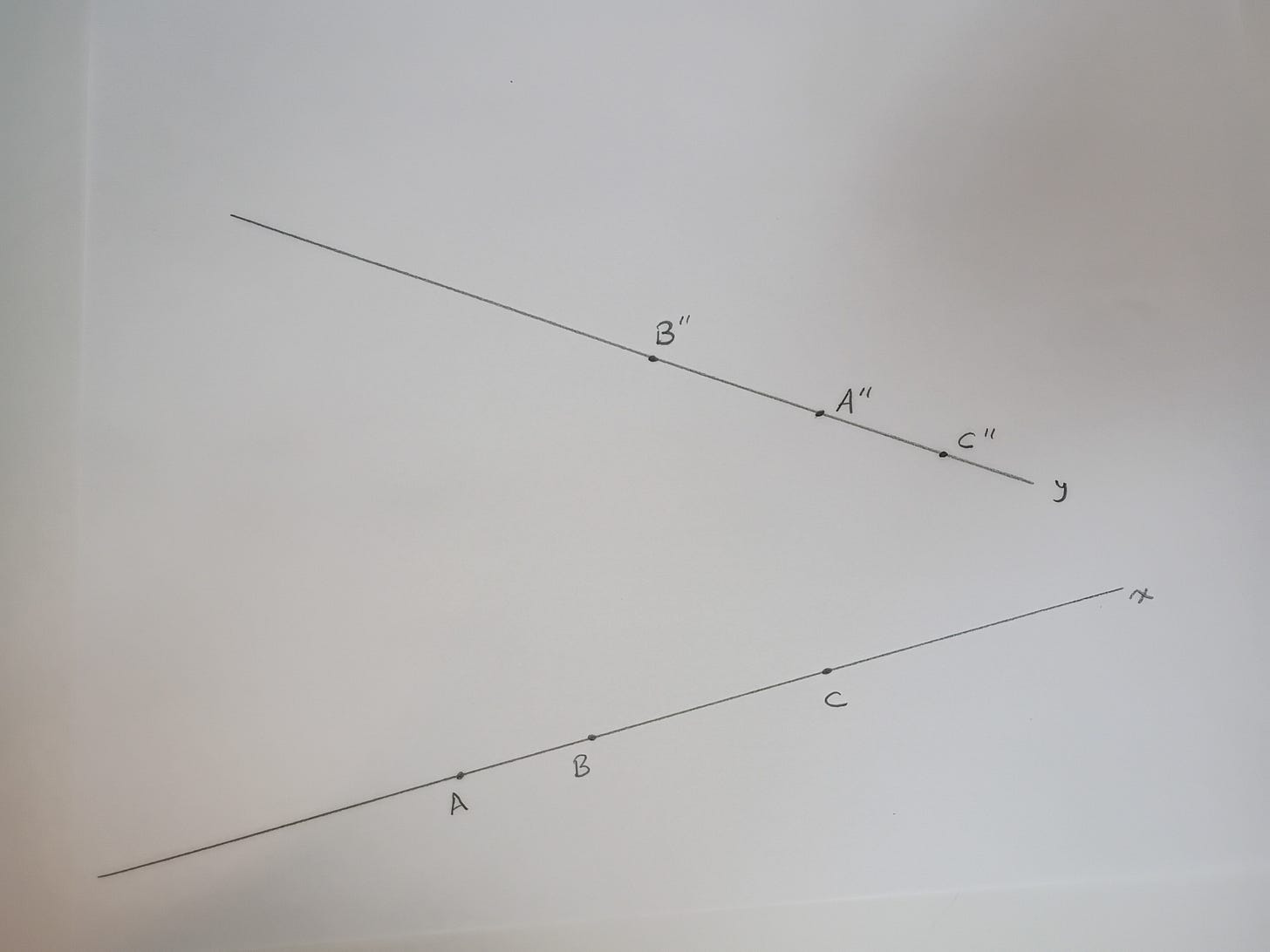

Draw a line any which way you like, call it x. Then place a point on that line, call it A.

Now choose a point that isn’t on the line and label it P. This is your Perspective point.

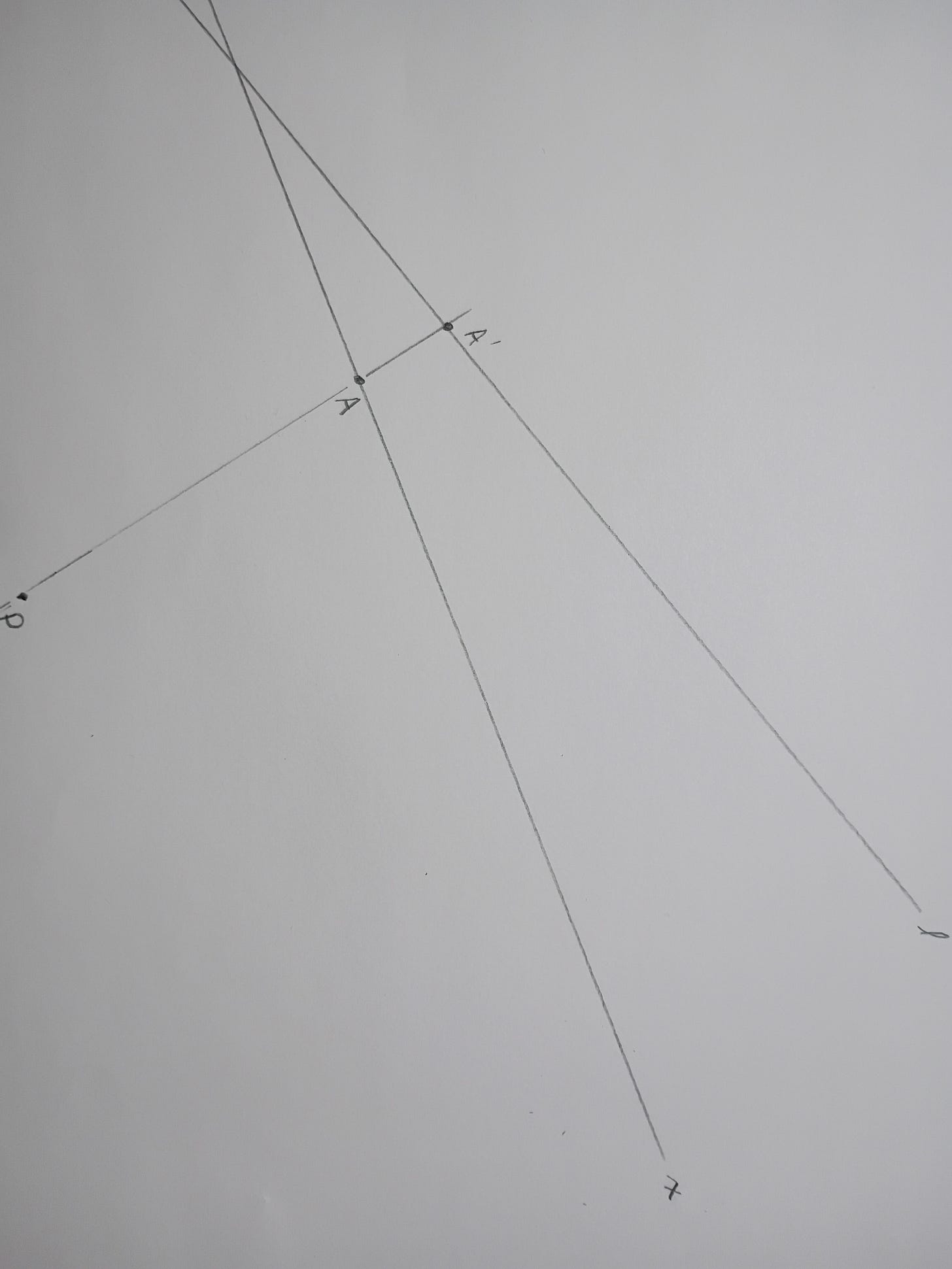

Now draw a second line, again any which way you wish. Call it l.

Draw a line through P and A until it intersects l. Call this point A’ (the way you read this is “A prime”)

What you’ve done here is the most basic move you can make in Projective Geometry. It is called a “perspectivity”. A perspectivity is a connection, from an original point to a “perspected” point through a point of perspective. We say “Point A on line x is perspected through point P to line l and becomes A’.”

Make sense?

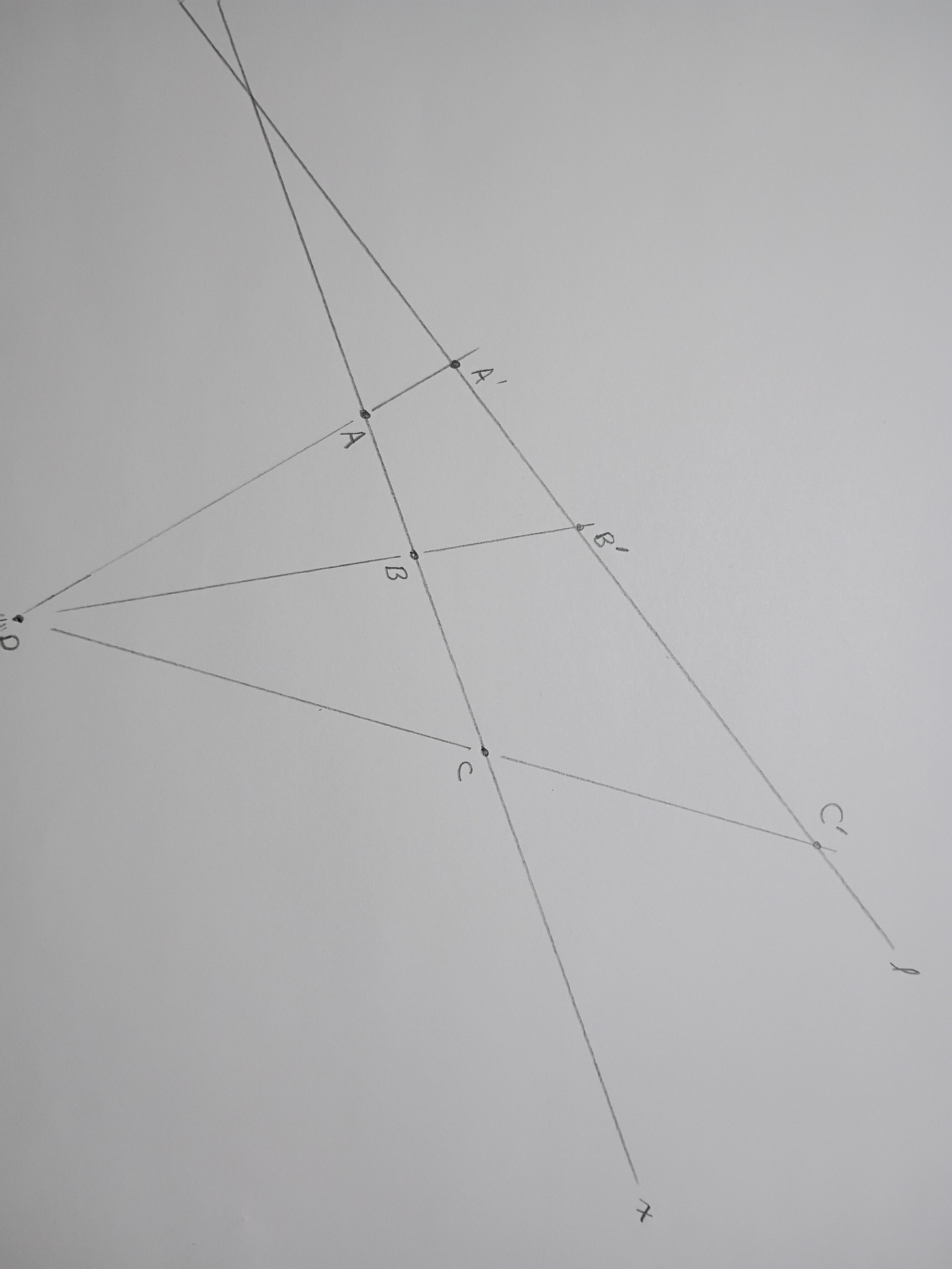

Now, you could keep doing this with more points on the original line, x: B, C and so on, and perspect them to line l. With a few examples and some thought, you realize that every original point on line x has a perspected point on l. The points may not be at nearly the same distance from each other, but every point on the first line has a corresponding point on the second. One way to imagine this is that the perspective point is like a Sun, and the prime points are like the shadows of the originals.

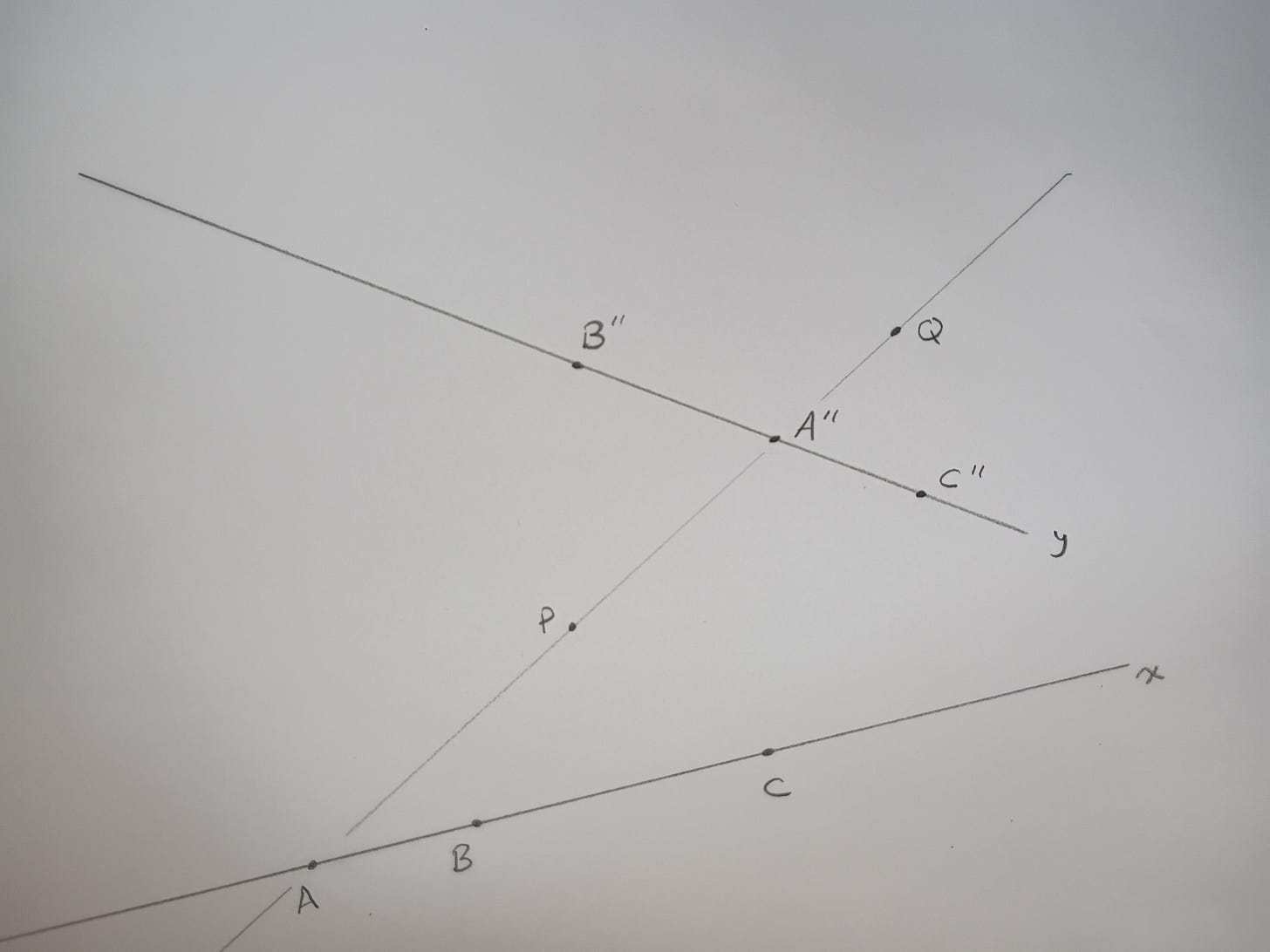

Now, choose a new perspective point (let’s call it Q), and draw a third line, y, and do the same thing to the prime points that you did to the originals. Perspect each of the prime points through point Q to get A’’ (the way you read this is “A double prime”), B’’, and C’’.

Oops, I forgot to label Q there, but you can figure out it’s the one that all three lines from the prime points to the double-prime points pass through. When you find Q, you may note that the idea I just mentioned of a Sun casting shadows only gets you so far (because the way I’ve drawn it, Q is between the prime and double prime points), but the idea is still the same. All lines “stream through” the perspective point, connecting the points on one line to new points on the next.

(As with all of these PG drawings, it’s really worth it for you to do it yourself. If you do, you will start to realize that, while you can place your perspective points, your lines, and the points on the lines anywhere you wish, depending on the placement, the way in which the points get perspected is different.)

So: We have done one perspectivity, and then another one in succession. With a little practicing, this can become familiar and comfortable enough. Often when you place the lines and points randomly, you end up not being able to find the perspected point on your paper. But, you can mentally imagine or “see” that A’ can be found, if you can just extend your lines long enough. This is also an important exercise that I’d encourage you to think about as you draw a few perspectivities…the idea of extending your paper-plane “as far as you like” to find the points of intersection.

All right. Once you’ve done this a bit and become comfortable with perspecting some points from one line to another, and then perspecting them again to a third line, you’re ready for this step, which is essentially working the same drawing from the other end. This is not so much an exercise as a proof. Your first proof in projective geometry! Of course, we probably all learned about proofs in high school geometry courses, and I think many of us were mildly to intensely tortured by them. I do not intend to bring back up any math-trauma you might be carrying around, but this proof, however much you follow it, is, I think, essential to the idea of “Just How Big Space Is.” This proof is entirely pictorial in nature, but it’s the thinking that comes along with the picture that is the key.

We are working in 2-dimensions, but this proof is valid in 3 dimensions as well. More on this in another future post, I hope.

So, now what you do is this: Draw the original line, x, and place three points randomly onto it, A, B, and C.

Now, draw the third and final line, y, and randomly place points A’’, B’’, and C’’.

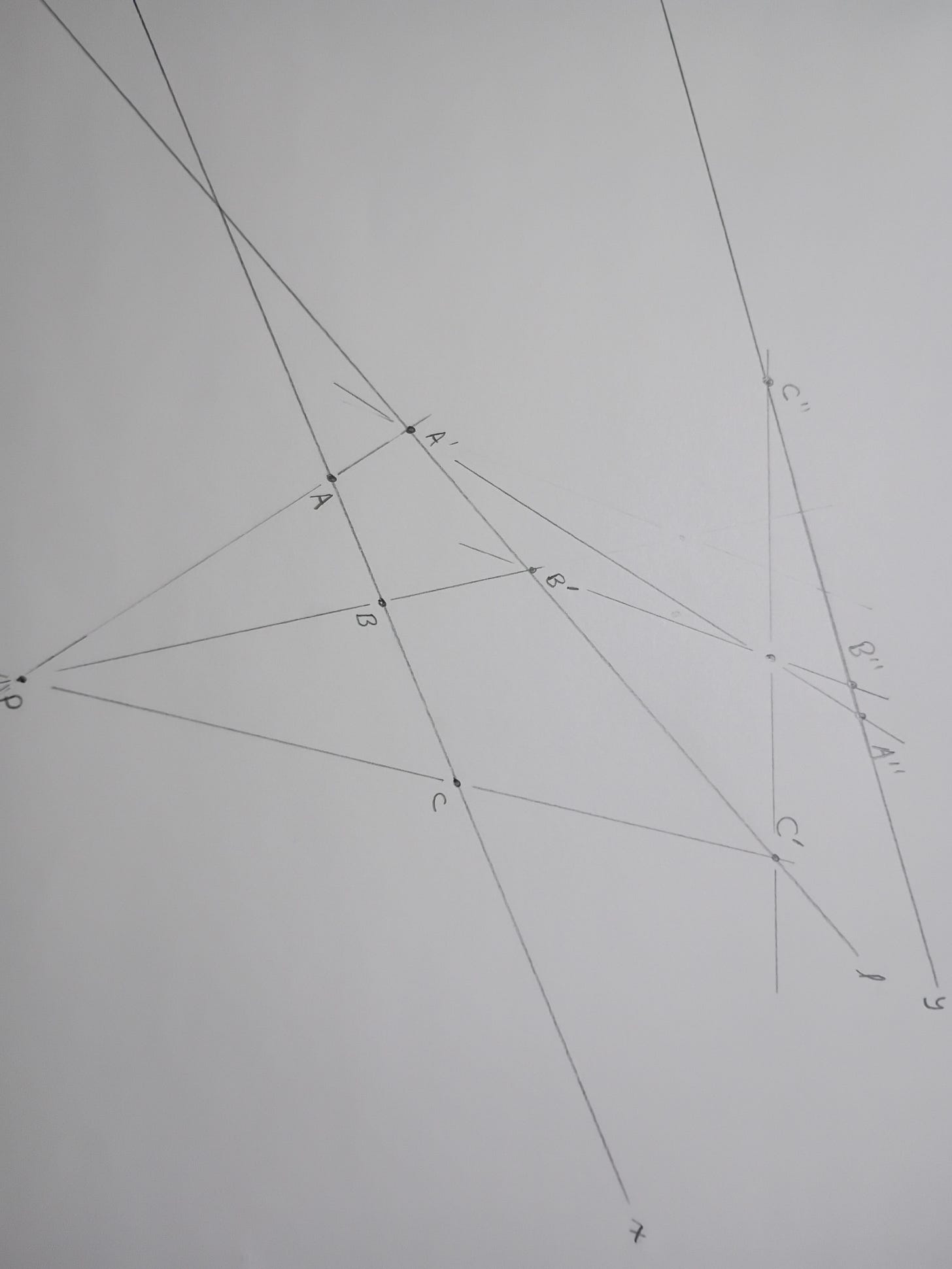

We will show that, although you placed the original points and the “double prime” points randomly on entirely randomly-placed lines, you can always connect them with no more than two perspectivities. Once we’ve done this, I’d like to impress upon you the significance of this proof, and it’s not just me, remember; this is called the Fundamental Theorem of Projective Geometry, after all.

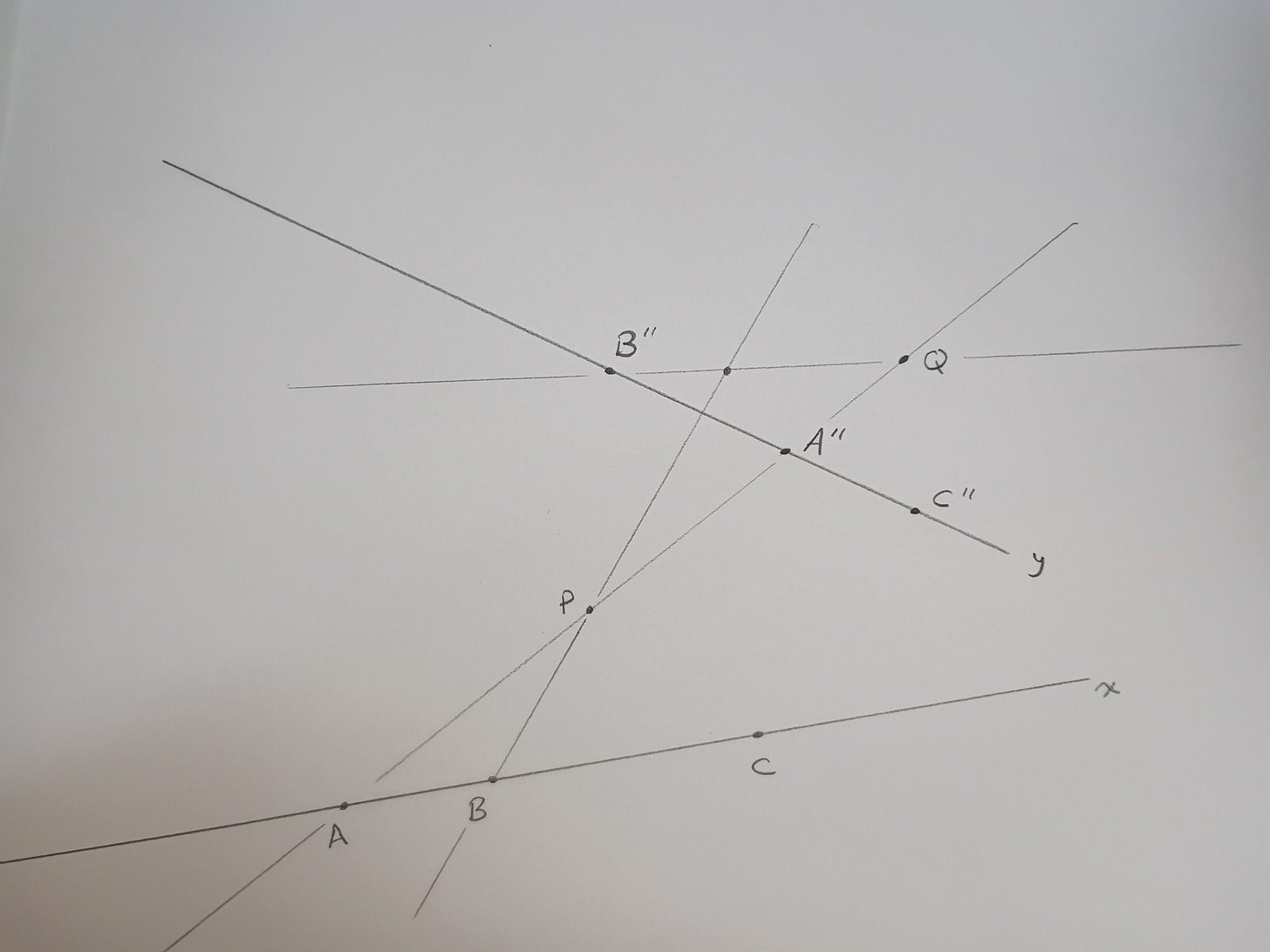

In order to prove the above statement, we must somehow find the intermediate line, l, and the perspective points P and Q such that we can perspect points A, B, and C to A’, B’, and C’ through P onto line l, and then perspect those “prime points” to the “double prime points”onto line x, through a carefully chosen point Q.

Here is how you do it. Again, it’s drawing it yourself (perhaps several times) and then studying it that is going to show you the meaning of this proof.

Draw a line that connects A and A’’ directly. Then place both perspective points, P and Q, onto that line anywhere that seems good.

Now, this is where some Projective Geometry kung fu takes places that shows that, despite setting up everything entirely randomly, these two sets of points on two lines are intimately connected.

We are going to leave the A points alone for the time being, but they will return at the end.

Draw a line through P and B, and draw a line through Q and B’’. Find where these two lines meet and mark a point.

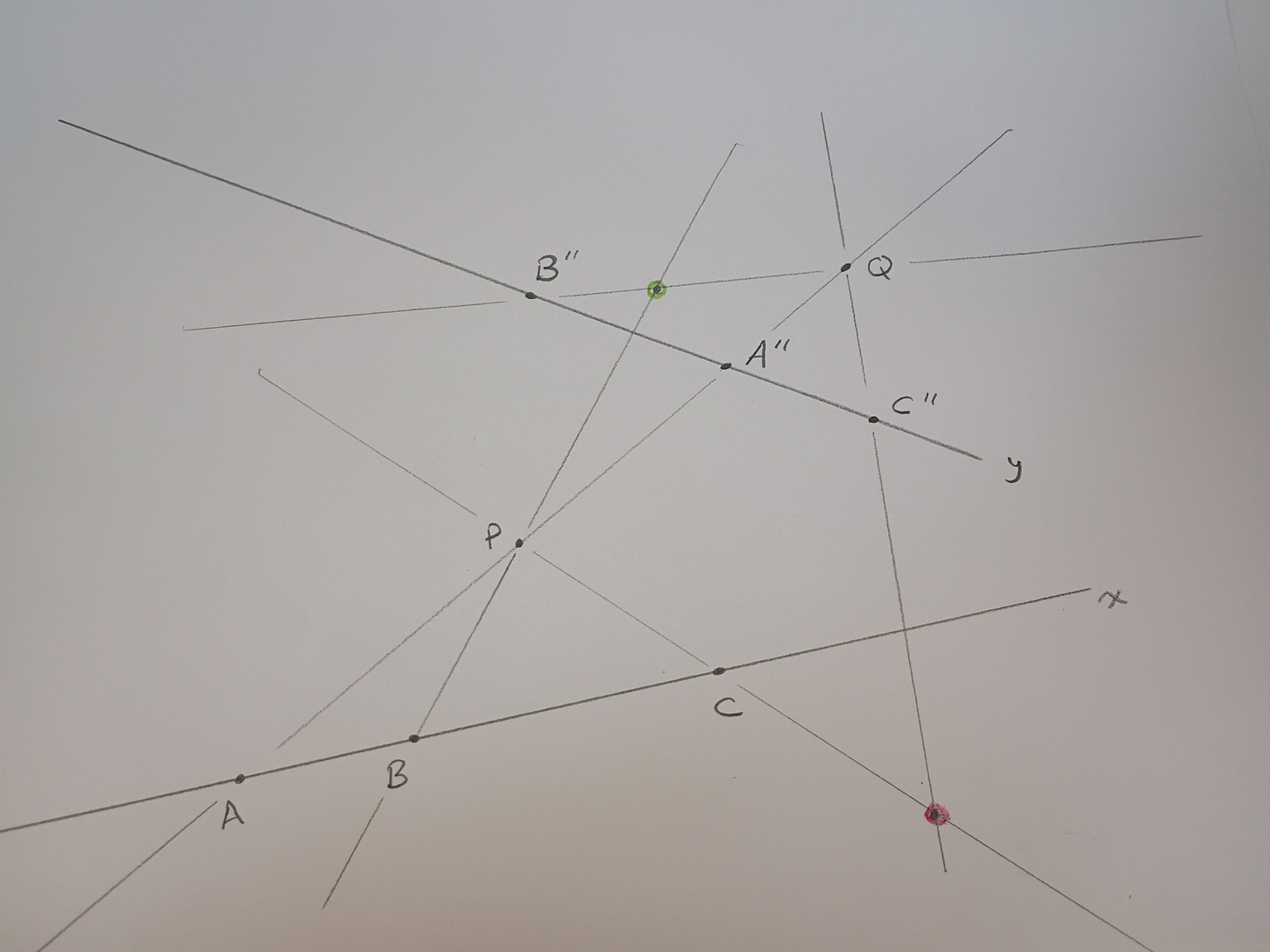

Now draw a line through P and C, and draw a line through Q and C’’. Find the intersection of these two lines and mark another point. In this picture, I’ve highlighted the two new important points with green and red, respectively.

Draw the line that connects these two new points. Now, regard what has been done: Because the points on this line connect to B and C through P, and also connect to B’’ and C’’ through Q, the line you just drew must be the intermediate line, l, and the two points you just found are B’ and C’. And, because you placed P and Q on a line connecting A and A’’, A’ can now be found on l.

You’ve done it! You’ve proven by drawing and thinking that, given any three points on any line, and any three corresponding points on any other line, you can connect them in only two perspectivities!

(If you can’t see how this drawing constitutes a proof, I suggest this: Say these words and look for the corresponding parts of the drawing. Convince yourself that all these things are true: Points A, B, and C lie on line x. Points A’’, B’’, and C’’ lie on line y. Lines through point P connect A to A’, B to B’, and C to C’. Lines through point Q connect A’ to A’’, B’ to B’’, and C’ to C’’. If all of this is true, then we’ve established a two-step perspectivity connection!)

This Theorem is so fundamental, that mathematicians have given two perspectivities in succession another name. It is called a “Projectivity”. Hence, Projective Geometry is born.

You may be saying, “So what?” right now. I really encourage you to let this drawing proof sink in. Here are a couple dawning realizations:

You could have chosen any points on any line anywhere, no matter how far out they were (you are working on a physical piece of paper, so you chose your points to help you work within these physical constraints, but you don’t have to do this in your mind as you think about the significance of this proof) This means that every and any line anywhere can be connected to any other line anywhere else, by simply choosing three corresponding points on each. You could have even chosen a line at infinity, something that perhaps we can do in a future post.

Also the number 3 is significant. We’ve already seen this when we were finding Harmonic points, that as soon as you put down three points on a line, other structures (like the Harmonic point) automatically manifest. You can turn this proof around the other way and say, “As soon as I place three points on a line somewhere and three corresponding points on another line somewhere else, I’ve established a firm comprehensive connection that can be revealed and then relied upon” If you were to then choose a fourth point on your original line, you could not place a corresponding fourth point randomly on the second line: You would have to follow the perspectivities to maintain the connection. In this sense, you’ve created a kind of map, that connects all the points on x to all the points on y. It is a complete correspondence that says “every single point on x has a corresponding point on y, and vice versa.”

I realize that this may not have the same effect as you as it does on me, especially if this is entirely new to you. It takes time to sink in. But everything we think, and know, and think we know about Space comes from our intuitions about space. And those intuitions are reflected in our culture: our art, our literature, our stories…and our mathematics. We created our picture of a mechanistic, random, meaningless universe from a Euclidean concept that comes ultimately from notions of physicality that strongly claim that if something is “far away,” it cannot affect you. But this proof and the Fundamental Theorem of Projective Geometry beg to differ. In fact, patterns that we set up in our minds, and patterns that we observe in the night sky, are and always will be, inextricably tied together.

If Space is in fact, intimate, connected, and chock full of patterns that arise after putting down just three pairs of corresponding points...everything suddenly feels different, does it not? It certainly does to me. One perhaps wonders about and reconsiders the popular dismissing out-of-hand of notions of astrology: that the heavens might have deep involvement and interest after all in life on Earth, in human thinking and human affairs. . . since that very thinking and those very affairs may be projectively connected to the thinkings of the heavens themselves. One place I could name that takes these cosmological connections seriously is Biodynamics. Here is a Biodynamics organization, the Josephine Porter Institute that I personally follow and you could too. Biodynamics came out of the work of Rudolf Steiner just like Waldorf schools did, so they are kissing-cousin movements. One can purchase a Biodynamic calendar, in which the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, planets and Zodiac constellations are charted carefully to indicate the best times to plant, harvest, fertilize etc. Do I think there is real truth and power in this approach to gardening and farming? Yes, I do. Do I think that because all plants and trees are fundamentally “beings of the Sun” they are likely also “beings of the whole cosmos”? Yes, I do.

Embracing the idea of a Space that is intimately connected, the human being simultaneously grows larger while the heavens come closer. One wonders how the heavens and the stars through the eons, ever present, have contributed, infused, formed and transformed all living beings on Earth, and continue to do so. If every plant, every tree, every animal, and every human are not only “stardust” in the physical sense, but also “star infused, star connected and star inspired” in the immediate and imminent sense…one may realize that although we humans may not be at the physical center of the universe, we may well be at the “center” of the streaming connections that saturate the heavens and our minds and bodies.

There is much I can do to play further with the Fundamental Theorem now that I’ve got it out there. If I lost you somewhere along the way with the proof, don’t sweat it. Hopefully further playing we will do will return again and again to solidify these understandings.

I will end here with the following quotation from Rudolf Steiner, as found in the book The Plant Between Sun and Earth by George Adams and Olive Whicher. Adams and Whicher’s book has made a huge impact on me, and has made me ever more confident that the intimacy of the cosmos is a present living reality, even if we’ve convinced ourselves temporarily that such connection is “impossible”. I hope I’ve provided a thread to follow that could, perhaps, allow a person to entertain such “wild ideas” as placing the human being back at the center of our cosmologies and in touch with the stars.

“When we look out on lifeless Nature, we find a world full of inner relationships and find in them the content of ‘Laws of Nature’. We find, moreover, that by virtue of these laws lifeless Nature forms a connected whole with the entire Earth. We may now pass from this earthly connection, which rules in all lifeless things, to contemplate the living world of plants. We see how the universe beyond the Earth sends in from distances of space the forces which draw the Living forth out of the womb of the Lifeless. In all living things we are made aware of an element of being which, freeing itself from the mere earthly connection, makes manifest the forces that work down on to the Earth from realms of cosmic space. As in the eye we become aware of the luminous object which confronts it, so in the tiniest plant we are made aware of the nature of the Light from beyond Earth. Through this ascent in contemplation, we can perceive the difference of the earthly and physical which holds sway in the lifeless world, from the extra-earthly and ethereal which abounds in all living things.”

Rudolf Steiner, March 1924

Photo by Weichao Deng on Unsplash

Thanks for reading Brian Does Whatever He Feels Like Doing, Gosh!! Subscribe to receive new posts and support my work. I don’t have paid subscriptions turned on right now, but if you would like to support me financially, without the intermediary of Substack, just reach out.

Why is it important to me to demonstrate what I am describing through a mathematical proof? I realize that many people do not have the interest, propensity, or confidence to find such a way of working to be compelling. But our world today is built on a kind of mathematical dogmatism, and so I find it incredibly freeing to experience that mathematics can also lead a person to freedom from that dogma.

Thank you kindly for sharing this lesson, Brian. I have fond memories of observing you teach projective geometry at CWS. You fostered a great sense of wonder in your students and myself.